When they say we are what we eat, they mean it. It turns out, we all come from lives lived towards putting food on the table, and making it look as good as it tastes. Just like we’ve held hands around a meal, food and beauty have also held hands with each other since the beginning of time.

Adam and Eve ate the forbidden fruit. Untouchable class became touchable through Renaissance paintings of fruit and chocolate, and all those delicacies eventually transformed into lipstick flavors and eyeshadow palettes we smudge onto our faces.

Our ideas of food and beauty are conduits to each other. They’re intertwined like DNA, and they have an odd synergy that can be only explained with profound spectacles like Lady Gaga’s meat dress and H-E-B butter tortilla candles - plus, the fact that we can all agree when someone’s ate and left no crumbs.

It's clear that we long to experience life in every flavor and texture. Yet, there’s something unattainable about satisfying our hunger. Henry David Thoreau said it best himself in Walden:

“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life.”

In our search for marrow in every season, we tend to change with them. We aim to be as chiseled as mountains and fresh as seafood in the summer; greening like trees and blooming like foliage in the spring; warmed and spiced like stew in the fall; and restful like sleeping animals in the winter. Even traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) urges us to follow the cycle of seasons in order to nourish our health - to use cold seasons as a time to find the middle ground between activity and rest, and eat warming foods that balance our yin and yang energy.

It’s no wonder, then, that many of us aspire to embody Hailey Bieber’s seasonal visions of a glazed doughnut or cinnamon roll, or blush boldly with Glossier’s flavors of mangos and strawberries during the summer.

We’re constantly being held in a seasonal cornucopia of fruit and dessert, just like we’ve always been.

An appetite for art

Still life paintings from the 16th and 17th centuries captured wealth by evoking fleeting freshness. They also arguably depicted women as delicacies themselves (what a surprise). Since still life paintings were more accessible than those that required models (restricted to male painters at the time), many of these women naturally turned into painters. And with more women becoming painters in the Still Life sense, it’s no wonder that today, we’ve held onto this tradition of bringing our own beauty to life as well.

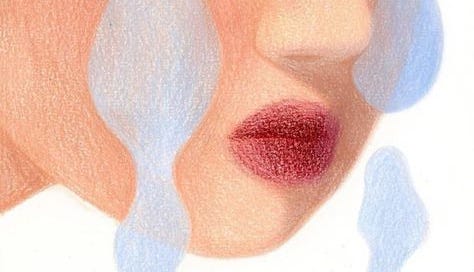

We’re a forbidden bold cherry from Glossier, daring to take a bite and toe the line between sweet and sultry. We’re also juicy, supple, strawberry cheeks from Rhode that wink with tartness - kissed, warm from being cradled by the sun.

I guess you could say, we’re all a moving still life. We went from paintings that lured us to dream of tasting an earthly richness of an upper class that our tongues may never touch, to cosmetic imagery seducing us in the same language.

But, none of this is new. The path fruits born by nature have taken from their roots in the ground, to the mouths of religion, to the pillows of our lips, to the immortality of art has been clearly marked before any of us put two feet on the ground.

Paint the lips red

In Reading Our Lips: The History of Lipstick Regulation in Western Seats of Power, legal scholar, Sarah Schaffer shows us a historical portrait of lipstick’s cyclical nature. Through every material and hue, our lips have articulated our perspectives of class, beauty, and even death across the landscape of time and geography.

Back in ancient Egypt, pots of lip paint accompanied well-to-do women in tombs into the afterlife. And known poisons like vermilion, mercury and arsenic in lipstick most likely continued to put anyone who wore them into the ground.

It makes sense that lipstick’s intimacy with death eventually translated to sin. During the Middle Ages in England, a woman who wore make-up was seen as an incarnation of Satan, because altering her face “challenged God and his workmanship.” The condemnation of lipstick ripened during England’s Victorian Age, where cosmetics were said to supposedly deceive male purchasers into overvaluing women’s worth.

This growth of criticism led to unwritten social codes on cosmetics being put down into legal form. And by written law, colored lips took turns being officially reserved for prostitutes, foreigners, the lower class, and eventually the elite.

Eventually, lipstick proved it had a valiant face. During the 1940s, manufacturers decided to sell lipsticks not as a “dishonorable frivolity,” but as a “vital part of the war effort.” Colored lips were symbols of resilient femininity, which boosted morale for both women and male soldiers during World War II. Painted lips meant strength and empowerment.

However, in the 1970s, feminists flipped and saw commercialized beauty as degrading to women again, opting for no-makeup looks. Lipstick meant sex and had the aura of forbidden fruit. It meant submitting to curated standards that no one wanted to stand for anymore. In turn, businesses responded to the anti-makeup spirit pulsing through women with claims of using more “natural” products, like plant-based and medicinal ingredients. They turned to celebrating the “liberated woman,” meeting them where they were (or really, who they wanted to be).

The life cycle of a cosmetic beauty today still lies in the oscillation between subculture and dominant culture. But, beneath the changing seasons of cosmetic beauty, what it means, and who should have access to it, I believe something deeper is continually at work.

A desire for authenticity

We’re not dying to taste the apple, strawberry, or cherry. When we drink up the molecules of the environment around us with our lips, painted or unpainted, I’d argue that what we really desire to taste is authenticity. We’re searching for ourselves.

We’re flipping through an interesting series of mental gymnastics.

We don’t care what other people think, yet we have to let everyone know we don’t care, and what exactly we don’t care about.

We say we’re focusing on ourselves, but we’re still proclaiming to everyone what exactly we’re focusing on and how we’re doing the focusing.

We stroke our own egos on the back like an unloved puppy, celebrating everything we’re not subscribing to anymore, but being more overzealous about telling the world about it rather than changing our behavior.

We say we feel liberated from beauty standards, but we’re really just creating new ones right under our very noses.

We’re outbidding each other on who can care the least about everything, yet still nurturing an abundantly curated life behind the scenes - all the while, secretly toiling away, still caring very much.

The new standard is for us to see who can hide all of this best, or perhaps, catch a glimpse of those who dare to not hide it at all.

Creating and concealing

Self-expression through beauty, food, and the like, have evolved to be perceived as authentic. However, there are too many mirrors (figuratively, and literally) for us to be authentic.

Beauty is supposed to be authentic. But, the conscious effort to be authentic - the self-aware, mirror gazing back at our navels, allowing us to constantly look into and at ourselves, is all actually very contrived, performative, and over-curated.

The truly authentic person is blind, because they can’t see into the mirrors. The truly authentic person expresses themselves especially when there are no mirrors around.

It’s the over-indulgent self-correcting, reminiscent of a ballerina searching for symmetry in the mirror, that gets us in the end - that is, the over-dependence on the mirror, and the lack of developing our own kinesthetic awareness, or knowing exactly how to move when mirrors can’t guide us.

When people come to a revelation and step up to the podium on any social media platform, announcing something like, I’m going to choose me, they’re really just choosing to subject themselves to public opinion. It’s the trying to be authentic, that actually renders itself inauthentic altogether. I’m taking a step back from social media / I’m done with Instagram / I’m not going to count my subscribers.

None of this is true authenticity, because we’re waiting for a response. And, admittedly, it’s hard for any of us to reach authenticity when there’s no authentic self to pull from, and we’re waiting for an affirmation of authenticity from someone outside of ourselves. It’s uncertain whether we’ll ever really know ourselves enough at all.

As Joan Didion mentions in The Women’s Movement, nobody forces women to buy “the package.” Most of us are waking up to that fact, and yet, we’re still enslaved to the package without realizing it. We have to accept that we are forever externalizing our fears and worries onto the world around us, and that it reflects them right back to us; that we, indeed, want not “a revolution but ‘romance,’… in {our} own chances for a new life in exactly the mold of {our} old life.”

All of this to say - maybe, you aren’t what you eat. You are what you see, and you are what you know. Because we will never see ourselves for who we are, or truly know ourselves outside of every mirror we’re stuck in, we become nothing and everything, all at once - which is, in the end, pretty much the same.

Style has always bursted from authenticity, but true style, and liberation, comes from within you, not beyond you. So, everyone’s kind of right when they say: you do you.

We have the choice to be us. We can be everything we want to be, whether people know about it or not. We can gladly stick to another piece of insight from Henry David Thoreau’s time in the mirrorless woods:

“Live in each season as it passes; breathe the air, drink the drink, taste the fruit, and resign yourself to the influence of the earth.”

We can decide which fruits are sweet enough, and how sweet we want to be in comparison. And we can identify what’s beautiful to us, and how beautiful we already feel being ourselves.

Just some food for thought.